Over the past three years, I’ve taken three different language exams—English C2, French B2, and Hungarian B2—that, perhaps unsurprisingly, offered me something beyond just an attractive diploma.

You don’t need any certificate to learn a language. Examples abound of people who have learned languages through non-institutional means—like watching television or listening to the radio—and have become almost perfectly fluent. Not having a piece of paper to prove it doesn’t diminish their achievement.

For most people, certificates serve a professional goal. For others—like myself—it’s more about having a structured aim to work toward, while also verifying that there’s no gap between my actual linguistic skills and my perceived level.

These exams cost money, are built around a clear framework, and, once they start, time becomes precious. In this way, they serve as an excellent tool for creating deadlines, providing structure, and adding pressure.

But one often-overlooked benefit—when these exams are prepared for properly—is their ability to help students develop deep critical thinking skills.

When it’s no longer about the language

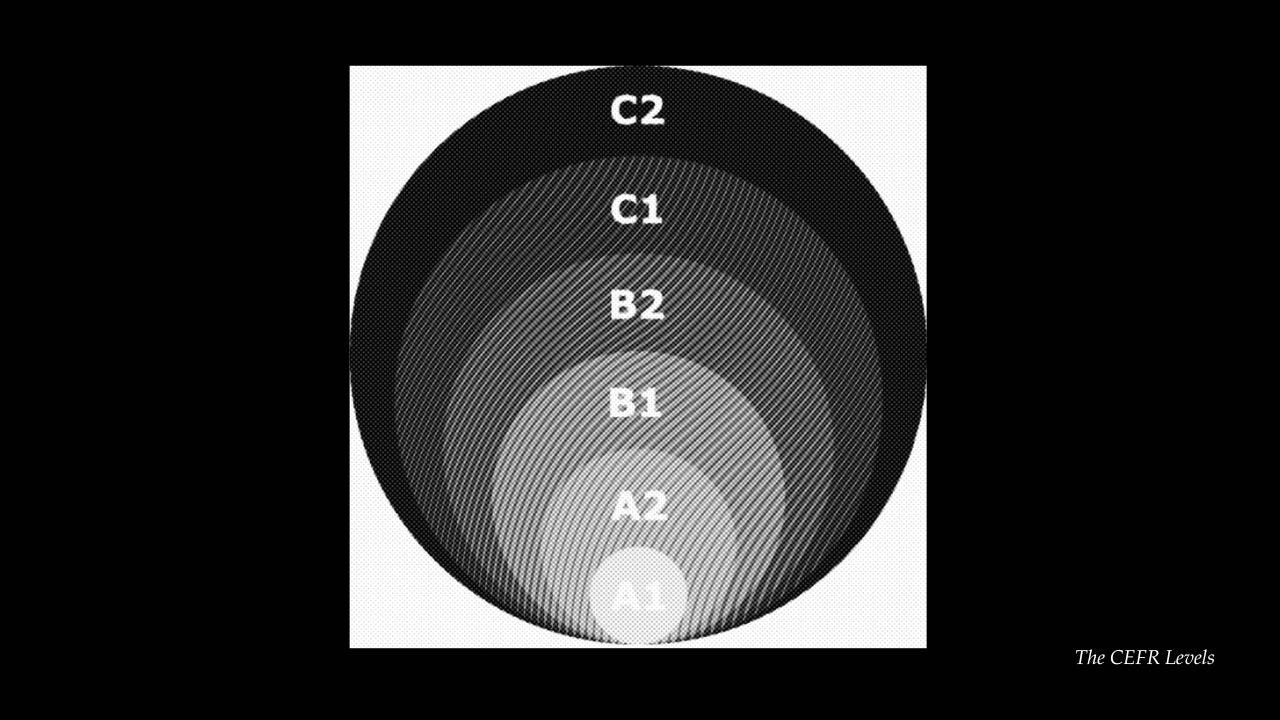

According to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages—the guideline we have in Europe for understanding language levels—when we pass the point of B1, we encounter requirements based on expressions like “abstract topics,” “technical discussions,” “implicit meaning,” “summarise information,” or “express themselves spontaneously.”

We are provided with tedious exercises where we have to take an active position and give our opinions on a variety of topics—sometimes trivial and weird things. But my experience tells me that it’s not really about the language—although you do need more specific vocabulary—but about providing structure and clarity to what you say, write, and understand. We are essentially asked to polish our thinking and improve the skills needed to pass on that thinking.

While it may seem stupid to talk about random pictures that somehow relate to the topic at hand, it’s a perfect exercise for improving our ability to think creatively and problem-solve under pressure.

Thinking Critically

After doing hundreds of role-play exercises and exploring how to structure different ideas for my last exam, when it came to the output part—writing and speaking—my brain was so used to structuring, synthesizing, and linking different ideas that the fact that I was under time pressure didn’t even matter—my brain was on fire. My pen and my mouth were moving as if I had somehow untethered myself from my body.

This, of course, required a lot of practice—a lot of reading and reflection after the read. And that’s the hard part: the critical thinking.

In my personal experience with the educational system, I can only say that not enough emphasis is put on the crucial skills needed in a digital, information-based society: separating the wheat from the chaff, synthesizing, creating links between different ideas, and thinking creatively. The only reason why these goals are on my radar is thanks to my interest in languages—I need these skills to pass the exams.

Thanks to the framework they offer, I’ve been paying more attention to diversifying my channels of information, checking the sources of what I consume, and thinking about my own personal opinion on different subjects—not all, though; I don’t feel like having an opinion on everything.

I can’t overestimate the importance of doing this with whatever we encounter on the Internet these days. Fake news, biased data, and uninformed opinions will probably only get bigger in number—and not necessarily because the world will actually get worse, but because our abilities to truly be rational and think for ourselves will keep on diminishing—unless we take responsibility for our thinking.

I am still early on my journey to developing this skill. I don’t watch the news every day, nor do I know how I feel about major and complex international events—precisely because I am seeing the many sides of the same things. But I am still trying daily to think slowly and deeply about the way our world works, and how my thinking can positively add to that.